This post is inspired by Kevin Zelnio, who shared his journey to science as part of an ongoing conversation after Science Online 2012 , and encouraged others to do the same (thank you, Kevin). To get the big picture, follow the #IAmScience hashtag on Twitter.

I am a high school biology teacher. This is what I tell people when they ask me what I do. It’s a reasonable answer. I go into my classroom every day and talk about biology. I draw cells and spindles and Punnett squares and trophic pyramids. I diagram squid and lancets and tiny choanocytes. I supervise activities that the publishers insist on calling experiments. I bring in blog posts and articles for my students to read and (with luck) argue over. Armed with play-doh and pop-beads, I tackle meiotic divisions and ribosomal subunits. I grade labs. I grade homework. I grade tests. I grade make-up tests. Darwin is my homeboy, and Mendel is my patron saint. On the surface, it’s all biology.

But, this isn’t where I was meant to end up. By the Year 2010, I was supposed to be a world renown marine biologist and film-maker, possibly married to Jean-Michel Cousteau, and definitely living 24/7 on a boat. I was supposed to be a champion of wildlife and a household name. I had resources. I had aptitude. And, I had a plan.

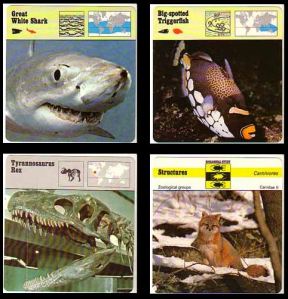

My love of science began with dental school. Not mine, of course. My parents were both doing postdoc specializations at a competitive university in the States. My early childhood memories of them involve lots of articles, slide carrels, and huge books with bible-thin pages covered in tiny print. My sister and I learned to read early, so they threw every science book they could afford in front of us to keep us entertained. Safari Cards were the absolute best . We had a pretty big set – maybe 2,000 cards. We pored over every one, reading and rereading until the corners were peeling and curling. My favorite was the Great White Shark, so I decided (at the age of 6) to become a marine biologist. I had no real idea what marine biologists did, but I imagined that if animals and seawater were involved, it was all to the good. For the next 10 years, every trip to an aquarium, every dolphin show, and every seashell collecting expedition reinforced my conviction that I was meant to be a steward of the ocean and all its teeming life. Yes. Steward of the Ocean. I imagined it on my business cards. My childhood was filled with museum trips and planetarium shows. A trip to Egypt coupled with my introduction to Indiana Jones briefly derailed my plans with fantasies of archeology, but a timely move to Miami during middle school got me back on track. The ocean was my back yard.

. We had a pretty big set – maybe 2,000 cards. We pored over every one, reading and rereading until the corners were peeling and curling. My favorite was the Great White Shark, so I decided (at the age of 6) to become a marine biologist. I had no real idea what marine biologists did, but I imagined that if animals and seawater were involved, it was all to the good. For the next 10 years, every trip to an aquarium, every dolphin show, and every seashell collecting expedition reinforced my conviction that I was meant to be a steward of the ocean and all its teeming life. Yes. Steward of the Ocean. I imagined it on my business cards. My childhood was filled with museum trips and planetarium shows. A trip to Egypt coupled with my introduction to Indiana Jones briefly derailed my plans with fantasies of archeology, but a timely move to Miami during middle school got me back on track. The ocean was my back yard.

I was lucky enough to be admitted to the MAST Academy in 1991 for high school. An old, converted aquarium attraction, this magnet school for “maritime science and technology” housed marine themed majors. For a kid who loved school, but hated homework, it was a pretty good gig. Flush with money, and staffed with young, enthusiastic teachers, I got to take three sciences in one year (seven, total, before graduation), read Moby Dick with the saltiest dog of an English teacher you could want, take part in the nation’s only Coast Guard JROTC, and go canoeing during physical education on Biscayne Bay. My chemistry teacher had the dubious distinction of having once been fired by Jacques Cousteau. My physics teacher let us fire ball bearings down the hallway. My JROTC instructor was a naval engineer. We built a boat in Woodshop. Even in the grips of the egocentrism of adolescence, I understood how blessed I was to be in a place where learning was the method and the goal. Of course, that was before NCLB.

The summer after my sophomore year, I landed a paid internship at RSMAS working in a planktonology lab. On the first day, I was introduced to my microscope at the lab bench. There I would sit for eight hours each day, sorting plankton tow sample jars, looking for fish larvae and copepods. It was mind-numbing, dull work, but the grad students made up for it. They seemed eccentric and cool; utterly unconcerned with fashion or regular sleeping hours. My teenage self felt included in a secret world of academia with the absolute hippest kids on the planet. I spent seven grueling weeks in front of that microscope, and three glorious days out on a research boat before Hurricane Andrew hit and turned Miami inside-out. I graduated high school with a “major” in Oceanic and Atmospheric Science. Everything was going according to plan.

And then, I went to college.

For the first time in my academic life, I had to work really, really hard. I spent the first month of college wondering if there was some kind of introductory course I had missed. The one where they pass out the secret decoder rings and the College-to-English dictionaries. I found myself suddenly in the midst of women who were not only passionate, like I was, but also terrifyingly smart. And disciplined. And diligent. The pace of my whole world had suddenly sped up, and I was spending all my energy just trying to catch my breath. I flailed my way through organic chemistry, suffering serious doubts about my future in marine biology (or any biology). Zoology, micro, ecology, evolution. The concepts were still fascinating, but the pace was grueling. I never blamed my professors. I was convinced (and still, mostly, am) that the problem was me. I was drowning in the sheer volume of information I was expected to assimilate, and I simply lacked the tools to do it. Every semester was a nail-biting saga of stress and frantic studying. Going into my senior year, I was adrift, academically. I had all but finished my coursework for my degree, but had lost my way in the daily grind to survive my major. Though my college experience helped me grow, socially and personally, in ways I never could have anticipated, my childhood science dreams seemed flat, dull things. I was numb and so very, very tired.

Three things happened my senior year that saved me from myself.

I took most of my credits that year in the Studio Art department. On the verge of really screwing up at school, I had decided that if I was going to disappoint my science-minded parents, then I was really going to go all the way. I took painting, bookmaking, calligraphy, drawing, woodcutting, and signed up for a senior art project. I found something in these classes that I had been missing since I left Miami – room to breathe. I was still getting it wrong. Still flailing. But my art professors held my failures up as a mirror for me to examine. Work took on meaning again. The process became important again. A failure was not just a wrong answer, but something that had value. I knew it was doing nothing to further my science career, but it felt good to live in my own head for a while. I had missed, perhaps mourned, the process of discovery.

The one science class I did take that year was Coral Reef Physiology with Paulette Peckol, a marine biologist specializing in coral reef ecology and conservation. I chose it because it was the only senior seminar that would fit my schedule, but it was the last thing I was required to do for my major. I was dreading it. The class was small – maybe fifteen women. It met in a tiny, dusty lab with a western exposure. The afternoon sun behind beige shades gave it a sleepy, mellow feel – like an old parlour. Professor Peckol handed us a list of journal articles the first day and told us, not unkindly, to get to reading. After we were done with all the reading, she made us get to talking. We each chose topics within the scope of the course and prepared a lecture for the class. Dredging through journal articles, trying to decipher the language of the research, I learned more than I ever had in all my frantic note-taking in the three previous years. My classmates were alternately nervous, funny, polished, panicked, and engaging. But, every one of them taught me something. I talked about sea-stars.

Later that fall, my boss in the IT department called in sick to the office to ask someone (ANYONE) to cover the workshop she was due to teach that day. It was a workshop for the faculty who wanted to set up their own web pages for their courses. I was bored playing desk jockey, so I volunteered. I walked in to the computer lab not having any idea what I was going to say, but not terribly concerned. I knew what they needed to know, and all I had to do was tell them, right? The first thing I saw when I got there was a very well-educated man trying to turn on his computer by speaking into the mouse. I knew, instantly, that whatever I had thought I was going to do wasn’t going to work. I wish that I had a more clear memory of what I said that day. I remember that I smiled a lot. I also paced the room, winding my way around the rows as I talked. I answered the same ten questions a thousand times. And, when the hour was up, the class – my class – got up and left. One of the professors stopped on her way out and asked me, when would I be teaching again?

And, just like that, I became a teacher. It suddenly became clear to me that my place wasn’t in the lab. My place was in school. I had gone most of my life believing that I was meant to follow the examples of great scientific researchers. All along, what had inspired me were science teachers. Be they books or museum displays or people, it was the discovery that made me love science. Throughout my childhood, my teachers didn’t tell me. They showed me. And, I had discovered that I knew how to show people, too. I volunteered to teach every workshop I could fit into my schedule. That summer, I got a job teaching remedial science at a high school in a small town. Seventeen students in eight subjects in one classroom and no textbooks. The next summer, they asked me to come back again. I put out my resume with the help of a head hunter for private schools which led, eventually, to an interview. The school took a chance on me – a 22 year old with a biology degree and no formal teacher training. Once again, I had a good teacher. An experienced, phenomenally intelligent woman took me under her wing and gave me nothing short of an apprenticeship in my first two years.

So, here’s what I really do: I am a specialist of 9th grade cognition. I take concrete operational minds and guide them to their abstract operational fruition. I scaffold the baffling unknown with the old familiar. Blank stares become skeptical squints become upraised eyebrows of wonder. Or not. I can’t reach them all. But, I get most of them. Every year is the same, but every day is different. I have come to understand more science in the teaching of it than in all my formal coursework. And, in teaching, I have reclaimed the joy of discovery through my students.

Science is the elegant truth in the messy stramash of history. Folklore and bias are all reflected in the science of each culture. How science is applied tells us about our mores and priorities. Every year, in groups of twenty, my students pick apart the fabric of their living world and discover that they are critical cogs in a wonderful ecological machine. Over and over, I get to see my students marvel at the tiny workings of their cells and be horrified by the biological bombs that are exotic species. I accept their dissonance and skepticism, and I repay them with evidence and data. I give them the real meanings of words like theory and proven. After thirteen years of experience, I can anticipate them. I see their questions writ across their expressions, and I draw them out in lines of logic and sense.

Joyfully, I am a high school biology teacher. I Am Science.

I love your last 2 paragraphs! Such a great way to turn failure, or disappointment, into an opportunity, Great story, thanks for sharing!

Thank so much for reading. I’m glad I did this. 🙂

That was *beautiful* storytelling. I’m a bit blown away. Your second post? Please tell me you’re planning on writing more. A lot more. Really rather regularly please.

Thank you, so much, for reading. You are very kind. All of the marvelous writing coming out of scio12 is an inspiration.

Inspiring! It’s amazing to see just what can come from seemingly minor, random opportunities like your first workshop.

Thanks for reading! 🙂

Yeah. Wow. Great storytelling. Loved the “Darwin is my homeboy Mendel is my patron saint” line. And the speaking into the mouse. Awesome. And the specialist in 9th grade cognition. Ok. all of it.

My dad is a high school English teacher and I think feels the same about Huck Finn and Walt Whitman. Which is why it is so heartbreaking that reform just focuses on test scores. So glad I got to meet you at SciO, looking forward to reading more.

Thank you, Cedar. I am really glad that Kevin encouraged us all to do this. It was long overdue for me. Cannot wait to read yours. 🙂

Lali. Thank you so much for sharing this. You’re teaching right here, in these paragraphs. With all my heart, m.

Thanks for the kind words. I am glad you enjoyed it. 🙂

Love you and I loved this! Where the hell did you find those cards? I remember them so well…That and sitting through Saturdays watching Jacques Cousteau documentaries for hours!

can you believe it? You can still order them from a few places… for $2 EACH!!! Yikes. Thanks for reading – love you!!

An inspiring story and inspiring writing. As you say, “before NCLB.” My children have had brilliant teachers who see their subject matter and their students the way you do, and these teachers are struggling year by year to save their subjects and their students from becoming nothing more than collections of assessment data points. Still struggling, and not sure when the pendulum will swing back. If only all kids could experience the joy and wrestle of science, as well as the facts…

Thank you for writing this.

Thank you for reading. Now, having children of my own in the school system, I see the struggle from both sides. Something has to change.

Very nice read, thank you so much for sharing 🙂

And keep having fun teaching, good teachers are so rare!

Thank you for reading, I feel very lucky to love my job!

This was such a joy to read – especially the last two paragraphs, which were just pure scientific poetry! You’ve really expressed something I struggle with conveying to many of my fellow scientists- while I want very much to be a researcher, I want just as much to be able to communicate the love and passion that drives my science to others. The magic you describe in teaching is wonderfully inspiring, and I wish more university professors took it as seriously.

Er, Gravatar got my name wrong for some reason. I fixed it. 🙂

Thanks, so much, for reading and commenting. 🙂

A beautiful love story… well said… 🙂

Thank you for taking the time to read!

This is storytelling at its colorful, captivating finest… is it too late to go back to high school and have you as a teacher?

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment. You are very kind. 🙂

I’m really trying hard not to read too many of these before I write my own but my Twitter feed has been going nuts with referrals to your post.

Holy. Dear. God (or FSM, if you wish).

You. Can. Write!

Rich, gorgeous writing. A beautiful story. And, yes, two final paragraphs that are going above my new desk when my new building is done.

You sing the song that is in many of our souls. Thank you.

Your comments are very kind. I am glad that you found something of use in my story. So many of the stories I have read have been an inspiration and a reinforcement that there is no one correct path to science. 🙂

I’ve been hesitant to join #IAmScience because my story is so traditional, right up to the point where I left “science” (a.k.a. academic research) to be a radio reporter/web producer. That’s where I re-found personal satisfaction and the joy of discovery. I’ll be speaking to a high school this Friday and they asked me to talk about how I got where I am. Maybe I’ll even write it down 🙂 Thanks for the beautifully written nudge.

Better yet, can you have someone film it? After writing my own, I am eager to read other people’s stories too. Let me know if you post yours!

Found you via the Not Exactly Rocket Science blog. Loved this quote especially:

“I scaffold the baffling unknown with the old familiar. ”

Well done!

thanks so much for reading!

I guess I’m late to the party, but that was a really nice read. I’m currently finishing a Masters degree in Genetics/Neurobiology, but am planning on an indefinite break from research afterwards. I’ve been thinking about teaching, and this message really resonates with me. Good teachers are too far and few between, I guess both because it is a demanding and underappreciated role. But they are oh so necessary.

Thank you!

Do you have any thoughts on what age level you’d like to teach? High school was a natural for me – I had such a wonderful high school experience that I knew that’s where I wanted to be. Thanks for reading!

It is so special to read your story, 10 years after having you for biology and homeroom. How cool. Thanks for sharing! Sorry for all the gum chewing.

KATIE! Thanks for reading. I hope that you are well – stop by when you are in town – you know where to find me. 🙂

You just shared my exact life story. I too set out to be a great ecologist (got the Ph.D. and all) and now teach introductory lab courses to undergraduates. You summed it up and what a great summary it is!

It is very gratifying to learn that I am not alone. There was a time when I looked back on my dreams of a career in research as a failure. It took a bit of letting go to just realize that my strengths were elsewhere.

WOW! I am blown away (figuratively, of course), by your prose – descriptive and eloquent and just pure joy to read!

Thanks so much for reading and commenting! 🙂

Wow. That was beautifully written. I literally teared up!

I’m currently working on my doctorate in pharmacology. Like you, I have passionately loved science my whole life. But now in grad school I’ve found all these other people who also passionately love science, but they are smarter/more diligent/more focused, etc. It’s so easy to get lost in feelings of inadequacy. But during my time in grad school I’ve had the opportunity to teach, and I’m finding that I love it. The more I do it, the more certain I become that I want to teach. Reading this lovely post gives me even more motivation to keep at it. I want to do exactly what you describe in those last two paragraphs. Amazing.

Thank you for reading. In the last 10 years or so, I have found that teaching is part science, part art, and a large part grim determination. The more I learn about teaching, the more I find that there is so much I could be doing! If only I had just 15 students and all the time in the world to try new things!

Do you have any idea what age level you’d like to teach?

Wild applause! I work as an educator amongst scientists, and sometimes, I feel like I’m really not supposed to be there… like a fraud amongst the learned. Then I realize that I am the best conduit they could ever ask for. It’s nice to know someone else made that realization as well.

Thank you for reading! What kind of work do you do?

A fantastic read! Well done. Your write with a passion and fluency that is to be admired. I too am a biology teacher and I too get dismayed at the system in which I work in. But I also use my passion for the subject to reveal the wonders of the human body, of nature and challenge them to think outside the box, ignore the exam and live the subject. I like to think that at everyone I teacher at some point shares my passion for the subject, if even for a brief moment.

Thank you for sharing!

An Irish biology teacher.

Thank you so much for reading. I am curious to know about the testing system in your part of the world. Do you have state/federal (or equivalent) standardized tests as we do? What role do these tests play in the promotion of your students to the next grade level? In my opinion, the high-stakes tests are choking the life out of the American school system.